TDD (Test Driven Development), why bother?

Recently I came to know about TDD (Test Driven Development), a development methodology in Agile Software Craftsmanship. At first, I was not even sure that how can we write tests to detect bugs in the code, because we write very specific tests that don’t cover every possible use-case. I didn’t understand the purpose of such tests at all. But then digging more into the topic I discovered what is the utility of these tests which I’m going to share in this article.

What is TDD?

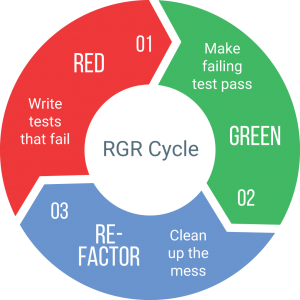

You already know the full-form of TDD. Now, TDD is a process that is used to create software with very small repetitive cycles which include: analysis of the requirement, converting that requirement into a very specific test case which shall fail, then we write the production code to make the test pass, we refactor the code and then again repeat the cycle with new requirement. After each cycle, all the tests must pass. We’re not that great at coming up with a code that has correct behaviour and correct structure simultaneously. To overcome this, we follow the RGR cycle in TDD, while always keeping the three laws of TDD in mind.

The Three Laws of TDD

These laws lock a developer into a cycle that is short but is very crucial to maintain. They are:

- You may not write production code until you have written a failing unit test.

- You may not write more of a unit test that is sufficient to fail, and not compiling is failing.

- You may not write more production code that is sufficient to pass the currently failing test.

The purpose of these laws is just to provide line-by-line granularity to the code. Almost every second you keep these laws into consideration.

RGR Cycle

Red-Green-Refactor cycle is repeated after every complete unit test or after a couple of the three laws cycles. They are:

- Write a failing unit test

- Write production code that makes the unit test pass, by any means necessary

- Clean up the mess, i.e. refactor the code

Source: Self-created.

Purpose of RGR cycle is to write clean code subject to constraints. As you write unit tests, you specify the behaviour of the software. And then you write production code which is constrained by the unit tests, so you can structure your production code while maintaining the behaviour of the software. Refactoring is done after each cycle, it is not to be left after the end of the project. It is this cycle that makes it easy to make changes in the code at any stage a lot easier while still maintaining the behaviour required.

Specific/Generic Cycle

This cycle is observed after every 10-15 minutes. It tells you that

As the tests get more specific, the production code gets more generic.

We’ll understand soon what this means with the help of an example. But in a nutshell, when you add even finer granularity to the unit tests, you should write more generalised production code to make the test pass.

Now let’s take the example of building a stack class using TDD.

I’ll use python in this example. Under a directory, I created two files viz. stack.py and test_stack.py :

stack.pycontains the production code and the classStacktest_stack.pycontains unit tests and the classTestStack

So let’s say the very first test is that the size of a new stack should be zero. Note that tests in python should be prefixed with test_

Create an interface method like this.

Now, run the automated tests provided by unittest module in python by command python -m unittest. Let me make the test fail by returning a value -1

I can make this test pass simply by returning the desired value 0, recall point 2 of RGR cycle.

Stack size after push is one

Let me write another test which checks if the size of the stack is 1 or not after one push.

Let’s make the test pass by simply incrementing the value of _size in .push() method and return that variable in .size() method.

Take a moment and notice that I replaced a constant value with a more generic variable. Also, I need to refactor the code now as I’ve duplicated code in both the tests. I can do this by moving the stack initialisation part in setUp method of the class TestStack, this method is called before running every test in the class.

Stack size is zero after a push and a pop

If I push an element and then pop it, the size should be zero after that.

Make this test pass by simply decrementing the value of _size.

Stack raises underflow error

What if the stack is empty and I try to pop a non-existing element? Yes, it should raise an error.

I write the following production code to make this pass by checking for the size equal to zero.

Stack raises overflow error

Great going till now, but what if the stack has a specific capacity and I can’t exceed its maximum capacity? I write another test just to check that and it should raise OverFlowError if pushed on a full stack.

Again, I’m introducing a variable _capacity in the constructor and I’ll check for it when I push on the stack.

Pop last element pushed into stack

Okay, till now every test is passing. But this stack is nowhere close to the actual definition of a stack. So, let me test if zero is popped when I had pushed it before.

This test will pass by simply returning 0. Note the point 3 of TDD laws here.

But what if a more general number, say 1 is pushed? It should return it when popped. I’ll write a test just for that now.

I’ll create a private variable _element and update it in .push() method and return it when popped.

True LIFO operation

Once again notice that I replaced the constant 0 with a more generic variable _element. But now, let’s make this Stack class really perform the Last-In-First-Out operations.

I will now modify the production code in the following way to make the test pass.

Did you notice what happened? I modified _element variable into a more general data type, an array. Now recall Specific/Generic cycle, as the unit tests become more specific, the production code gets more generic. I hope you understand now what was meant before. Also, the three laws were followed at every step of the cycles, recall that I returned a constant 0 to make the test test_size_is_zero_ after_push_and_pop pass. I didn’t generalise it by returning a variable right away. I just somehow made the test pass, that’s it. Finally, I can again refactor the code and since python provides some shortcuts with arrays, I can get rid of _size variable and all the unit tests still pass.

In other languages like C++, you’ll not get rid of _size and instead, can use it as an array index. In this way, even the initial code that I wrote is not a waste of time. I’m simply modifying the existing at every cycle and making sure the tests pass. None of the code that we write to pass the early tests is wasted code. It’s just incomplete and not generalised enough. After every cycle, the code evolves and becomes more general.

References:

- The Clean Code Blog

- Book: Clean Code by Robert C. Martin